According to international law, the countries, as a duty, must not allow their territories to be used against the national security of neighboring countries. According to the Declaration of Principles for Friendly Relations in International Law, no country should be a host nor a refuge place for terrorist groups. The 1944 Declaration on the Eradication of Terrorism called on countries to refrain from encouraging or approving activities that directly lead to terrorist activities in their territories. The Iraqi Kurdistan Region (IKR) is not a country, but it must be committed to the international law, as it has a federal structure in Iraq and its autonomy is in the framework of Iraqi rule, so the IKR must abide by the law.

Terrorist groups in the IKR: Qandil Mountain on the Iran-Iraq border is serving as the headquarters of the PKK / PJAK terrorist group, which has committed many terrorist acts against Iranian Kurdish citizens. Since 1998, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), led by Jalal Talabani, has established its guerrilla headquarters in the region. Kurdish rebels opposed to the Iraqi government have been active in the area since the mid-1980s, but PKK members entered the area extensively in 1991. [2]

Due to high pressure from the Turkish government, these people were forced to flee the country. From 1982 onwards, following the Iran-Iraq War, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the PUK gained more freedom of action because Iraq moved its forces to the southern front. [3] Thus, despite some differences, the two parties accepted to let the PKK terrorists be installed in the areas under their control.

Terrorist acts of groups present in the region: PJAK has carried out terrorist operations against the Islamic Republic of Iran in various ways in the region. In 2005, the Iranian government announced that at least 120 Iranian soldiers had been killed by PJAK by then.

In the conflict with the Islamic Republic, the group uses anti-war tactics, and its members return to their refuge in the IKR immediately after the operation. In addition, some sources claim that PJAK’s coordination with the anti-Iranian policies of Israel and the United States led it to receive advanced weapons from them [5].

On the other hand, it should be noted that relations between the Marxist PKK and Barzani’s Conservative Party have never been very cordial, but Barzani allowed Ocalan’s followers to operate from areas under his control south of the Turkish border (northern Iraq). During this time, PKK operations against Turkey gradually increased, for example, the assassination of 12 Turkish teachers in southeastern Turkey, planned by Ocalan in 1993-1994.

Another act committed by the PKK was to kill 26 villagers in a military operation and then spill gasoline on the houses of four village guards and set them on fire, while their families were locked inside their homes. [6]

Relative silence and passivity of the IKR: With the fall of Saddam’s regime in Iraq and the expansion of the rule of the KDP and the PUK, Iran expected the northern Iraq not to be a stable and secure base for the Iranian opposition groups; Or if these groups reside and are present in the IKR, they will not be allowed to carry out military and political activities against the Islamic Republic of Iran. An examination of the performance of the IKR and its ruling parties shows that Iraqi Kurdish leaders have made steady progress in this regard and, despite some restrictions, have not met the expectations of the Iranian government as a whole.

After the collapse of Saddam Hussein’s Ba’ath party, the Islamic Republic’s political and security officials’ expectations from the IKR’s leaders doubled, but contrary to the expectations of these officials in recent years, northern Iraq has become the field of the PKK terrorist group and its Iranian branch. PJAK and the organization of military, political and media actions against Iran, especially through the Tishk satellite TV Channel affiliated with the Democratic Party and Komala [7]

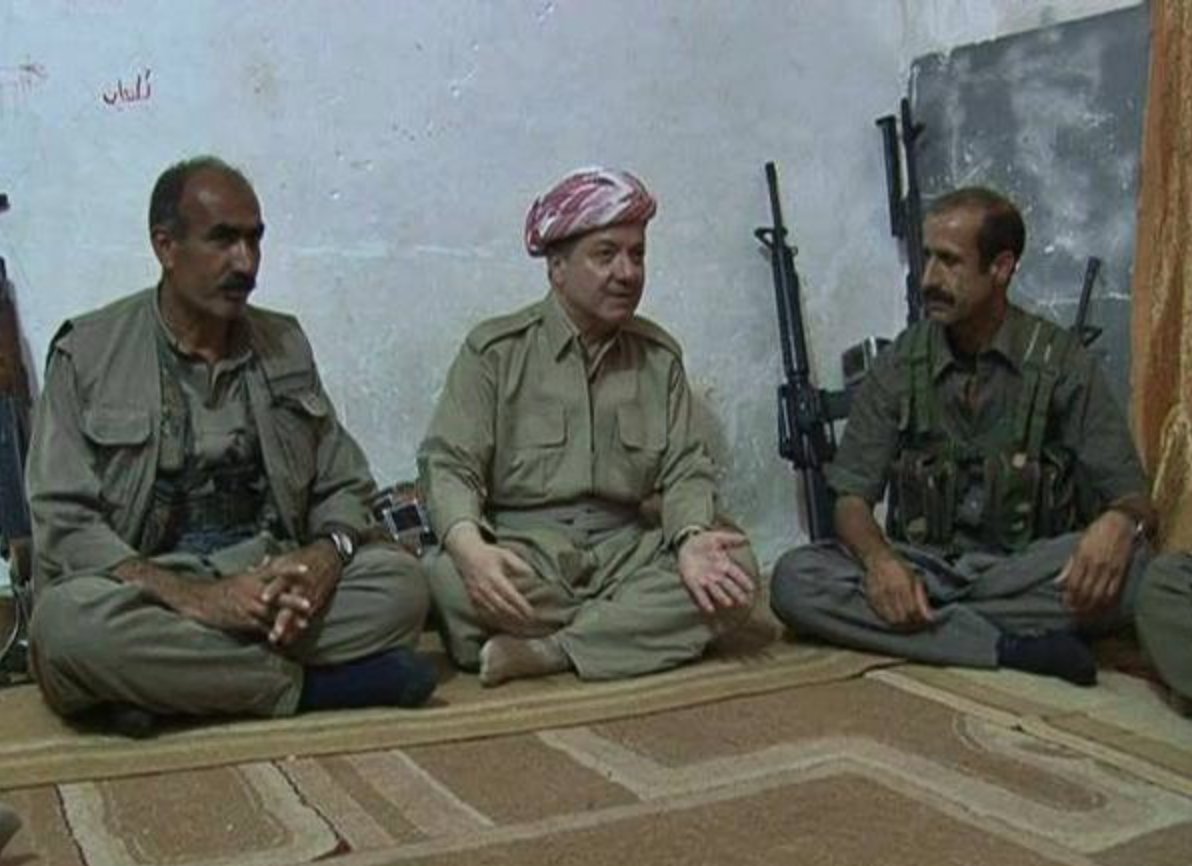

In an interview with the Turkish Independent Magazine in 2000, Massoud Barzani admitted: In Turkey, many Kurdish parties and organizations fled abroad due to the 1980 military coup. At that time, the PKK also took refuge in the Kurdistan Region, and we helped them a lot and considered them as our brothers. [8] Both the territory and the occasional (but obvious) support of the Kurdistan Regional Government to the PKK allowed them to organize and launch effective operations against Turkey and its opponents. At times, the IKR also took a critical approach to the reciprocal response of the victim governments (Iran and Turkey). Even now, just to maintain their appearance, they are criticizing the Turkish occupation of the region and its attacks under the pretext of fighting the PKK.

Reactions by neighboring governments to IKR’s silence: Developments in the Kurdistan Region, as a variable influencing Iran’s national security considerations, have led to policies and reciprocal responses by Tehran. Tehran’s response ranges from security cooperation with the Iraqi government, the IKR and the Turkish government to the organization and implementation of some military and intelligence operations, especially against the PJAK. Iran has always compromised with the Kurdistan Region on the issue of terrorists. And Tehran officials have repeatedly reprimanded Kurdistan Region officials; But in the end, if they did not see a positive step from there, they would, through their military forces, take defensive measures against the terrorist acts of PJAK and other armed groups.

The approach of Turkey and Iran towards the IKR: On the other hand, it should be noted that there has always been a big difference between Iran and Turkey in their view of the Kurds. In other words, unlike Turkey, which considers the Kurds to be a largely rebellious and uncontrollable minority, Iran has always considered the Kurds to be one of its historical and influential ethnics. In fact, if Turkey sees the Kurds as an ethnic, Iran considers the Kurds are part of the Iranian nation. [9]

During the 1990s, Turkey carried out numerous large-scale aggressions against the Kurdistan Region. Turkish attacks on the Kurdistan Region until 2007 included a total of 12 major operations and an unspecified number of operations at lower levels. [10] Underthe pretext of war against the PKK, Turkey has officially established military bases in the region.

Turkey did not limit its presence in Iraqi Kurdistan to mere political meetings, but more importantly to its military presence in northern Iraq, which has taken an institutionalized form with the Turkish army’s frequent and regular raids and raids on those areas, which usually took place twice a year. Although the Islamic Republic opposes the secession of the Kurdistan Region and emphasizes the preservation of Iraq’s territorial integrity, Iran’s policies in Iraq over the past decade and Tehran’s arms aid to Erbil at a time when the IKR was under the ISIL attack are the basis of the increased Iranian convergence with Iraqi Kurdistan [11]

Iran’s right to confront terrorist groups: One of the most important international instruments recognizing legitimate defense as a natural right of states is the UN Charter, in particular Article 51 thereof. According to this article, in the event of an armed attack on any member of the United Nations, as long as the Security Council has taken steps to maintain international peace and security, the right of individual or collective defense shall be vested in each aggrieved state. 1. International law does not explicitly count non-state actors, including individuals and groups, as initiators of war or armed attack. This means that this attack must be assignable to a government, in addition, the degree and impact of this terrorist attack must be comparable to intergovernmental conflict. [12]

Given this issue, there are four criteria that can explain the role of the government and the terrorist group: 1. The non-governmental actor may be part of the official authorities of the country or be employed by the host country. 2. The non-governmental actor may be independent but provided with financial, logistical, weapons and training assistance from the host country. 3. The host country may not actively support the non-governmental actor in the form of paragraphs 1 and 2, but before or after the armed attack provide a safe haven for the non-governmental actor and be a safe haven for them. In fact, the host country is passive and does not act against them. They should be unanimous. 4. The host country may not be able to exercise control over the non-governmental actor. [13] Of course, it should be noted that the right to use this principle has terms and conditions that are discussed in detail in the relevant international instruments.

Knowing that the Kurdistan Region is free from the positions and actions of the PKK and PJAK terrorist groups is a simplistic and reductionist approach. In the most optimistic case, the IKR falls under the third paragraph; and that gives Iran enough legal legitimacy to defend itself. Therefore, either the IKR must deal seriously with terrorist groups such as the PKK, PJAK and the Democratic Party of Iran (KDPI), or it will have no right to protest if Iran reacts.

Resources:

[۱] Declaration on Measures to Eliminate International Terrorism1994.

[۲] براندون، جیمز (۱۳۸۸). قندیل پناهگاه شورشیان کرد. ترجمه: موسیپور، موسی و جهانبخش رهنما. مجله اطلاعاتسیاسی و اقتصادی. شماره ۲۶۴.

[۳] جی زوخر، اریک. (۱۳۹۷). تاریخ نوین ترکیه. تهران. نشر سمت. مترجمان: نفیسه شکور و حسن حضرتی.

[۴] Brondon,james (2006).irans Kurdish threat: pejak. The Jamestown foundation. terorism monitor.

[۵] پور موسی، موسی؛ رهنما قره خانگلو، جهانبخش و میرزاده کوهشاهی، مهدی (۱۳۸۹). فعالیتهای تروریستی پژاک و امنیت جمهوری اسلامی ایران. فصلنامه آفاق امنیت. سال سوم. شماره نهم.

[۶] انتصار، نادر. (۱۳۹۰). سیاست کردها در خاورمیانه. تهران. نشر علم. مترجم: عرفان قانعی فرد

[۷] کوزهگرکالجی، ولی (۱۳۸۹). روابط ایران با اقلیم کردستان عراق. نشریه گزارش. سال نوزدهم. شماره ۲۱۹.

[۸] شیخ عطار، علیرضا (۱۳۸۲). کردها و قدرتهای منطقهای و فرا منطقهای. جلد اول عراق. مرکزتحقیقاتاستراتژیک.

[۹] بهمن، شعیب. (۱۳۹۹). ایران و ترکیه؛ خصومت، رقابت و شراکت. تهران. موسسه نور.

[۱۰] لطیف الربیدی، حسن و محمدالعبادی، نعمه و لافیالسعدون، عاطف.(۱۳۹۵). عراق در جستوجوی آینده. تهران. موسسه مطالعات اندیشهسازان نور. مترجم: علی شمس.

[۱۱] عبدالحسین زاده، شراره. (۱۳۹۶). در برج امنیت؛ چرایی ورود ایران به پروندههای منطقهای.تهران. موسسه مطالعاتی اندیشهسازان نور.

[۱۲] Schmalenbac, Kirsten(2002). The Right of Self-Defence and The “War on Terrorism” One Year after September11. German Law Journal

[۱۳] سواری، حسن و اصلانی، خه بات (۱۳۹۱). عملیات مسلحانه بازیگران غیردولتی علیه کشورها: تشکیک در قواعد حاکم بر توسل بهزور. مجلهٔ حقوقی بینالملل. نشریهٔ مرکز امور حقوقی بین الملی ریاستجمهوری. سال ۲۹. شماره ۴۶