Sirwan Kheirabadi, a 26-year-old man from Sanandaj, was killed in a Turkish air raid just five months after joining the armed PJAK group. According to his family, he was a victim of deceptive propaganda and the emotional distress resulting from personal failures. Today, he stands as a symbol of the hundreds of young Iranian Kurds who were taken to the mountains with the hollow promise of “freedom” and vanished in absolute silence.

Sirwan Kheirabadi’s story is one of the most chilling examples of the fate of young people who, amidst a vacuum of hope, employment, and social support, became fodder for the propaganda machine of PJAK and the PKK.

Born on April 14, 1986, in Sanandaj, Sirwan completed his high school diploma and spent the subsequent years searching for stable work, repeatedly holding temporary and precarious jobs. However, the economic pressures and a broken engagement drove him into an isolation that made him vulnerable to PJAK’s recruitment propaganda.

According to his father, in the days following his emotional setback, Sirwan was drawn into social media and political discussions, where PJAK activists used slogans of liberation and justice to encourage him to join the group. In March 2012, he left home without saying goodbye, and a few weeks later, he was reportedly seen in Qandil.

Just five months after leaving Iran, on March 1, 2013, news of his death was published by PKK-affiliated media. His body was never returned to his family, the group made no official contact, and there is no indication of his burial site. His father states, “They neither returned his belongings nor even a single sign. We still do not know where our son is buried.”

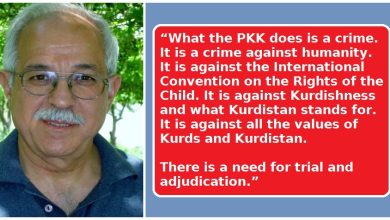

Sirwan’s death is not just a family tragedy; it is part of an organized pattern of deceit and emotional exploitation that these groups employ for recruitment in Kurdish regions. The use of young people’s failures and emotional wounds, giving them a new identity, and erasing their name and past, is a familiar tactic within the structure of the PKK and PJAK—where an individual is quickly transformed from a “human being” into a “tool of war.”

PJAK never accepts responsibility for the lives or fates of its recruits. As is clear in Sirwan’s case, there was no accountability, nor was there even the right to know for a family whose only request was information about their son’s fate.

Sirwan Kheirabadi is no longer just a name; he is a reminder of the youth who were sacrificed for politics instead of life—young people who, in search of meaning, fell into the trap of ideology and never returned.

Full Interview with Sirwan Kheirabadi’s Father

Mr. Kheirabadi, please tell us a little about Sirwan and his life.

Sirwan was my first child. Born on April 14, 1986, he was a quiet boy from childhood; he neither caused trouble nor was he prone to fights. He grew up in Sanandaj, finished high school, but couldn’t find work after that. At first, he worked in various shops to help with household expenses, but our family’s economic situation was never good. His mother was always worried about his future because she saw her son, with all his talent and intelligence, forced to move from one temporary job to the next.

What caused his life to diverge from the normal path?

It all started around the time of his engagement. Sirwan was engaged to a girl from the village of Serinjianeh. Her family were distant relatives of ours. It wasn’t a teenage crush; they had made a serious decision to marry. However, because our financial situation was poor, the girl’s family gradually began to object. The pressures grew until the girl was forced to break off the engagement. This incident was a massive emotional blow to Sirwan. He blamed himself constantly, saying, “Dad, I couldn’t even build a simple life. What kind of man am I?”

From then on, he became withdrawn. He gradually distanced himself from gatherings. He spent most of his time either in his room or on his phone. At the time, we thought he was looking for work or connecting with friends, but we later understood that he had been introduced to people on social media during that period.

Were you aware of these connections?

No, unfortunately not. Sirwan never told us anything. Occasionally, he would bring up discussions about freedom, oppression, and justice, but we never imagined these words were a sign of something more. We later realized that they had directly exploited this feeling of weakness and failure. People who know how to manipulate the emotional wounds of young individuals slowly deceived him. Sirwan was looking for value, for the respect he had lost in his ordinary life.

When did you realize he had left home?

It was March 1, 2012. We woke up in the morning and saw his things were gone. He hadn’t left a note, no news. He had only taken his regular clothes. At first, we thought he had run away or gone to another city for work. But his phone was switched off from that day. We searched for him for several days, called his friends, visited relatives, but no one had any news. After about a month, an acquaintance who had returned from the Kurdistan Region of Iraq said he had seen Sirwan crossing the Bashmaq border with several other people. That’s when we realized he had probably ended up in Qandil.

So, he left the country without any contact or farewell?

Yes. He never said goodbye. No call, no message. It was as if he deliberately wanted to cover his tracks. Only later did one of the young men who had been in the PKK for a while tell us that a few weeks after Sirwan arrived in the mountains, he received military training and was known by a new alias. They remove the true identity of members from the very beginning so there is no returning.

Did you see any sign of his decision before he left?

The only thing I remember is that in the final weeks, he spoke a lot about death. He would say, “Dad, some people have to be useful even when they die.” At the time, I thought he was talking about depression, but now I understand that perhaps he had made up his mind. Those groups target exactly such people: those who are desperate and searching for meaning.

Did you take any action to find him after he left?

We tried hard. But without documents, without a passport, and without anyone on the other side of the border, we couldn’t do anything. We contacted a few old acquaintances who worked in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, but they also said that travel in the Qandil areas was very dangerous. Turkey was constantly bombing, and PKK forces did not allow anyone near. News only reached us through television networks and media affiliated with the group.

When did you hear the news of his death?

About four or five months after he left; on March 1, 2013. A neighbor came and said that Sirwan’s name had been read on Newroz TV. I didn’t believe it. But when I watched the program myself, his name was there, along with three others. They said they were killed in a Turkish air attack on the Qandil heights. I can still hear his mother’s voice when she found out… she just cried and said, “Does this mean we won’t even see his body?”

The next day, the news was published on several websites, but we received no official contact from the group. No one said where he was killed, nor whether there was even a body left.

Did you follow up with them?

Repeatedly. We talked to everyone we thought had a connection. But they even took away our right to know. They neither returned his belongings nor even a single sign. We still do not know where our son is buried. We only know that he left on March 1st, and his name appeared on the list of the dead exactly one year later, on March 1st. There is no trace of him.

Today, after all these years, when you look back, do you think this wouldn’t have happened if someone had helped Sirwan?

Absolutely. If there had been someone to listen to him in those days, if there had been hope left in his life, if officials had done something for young people like him, he never would have ended up there. Sirwan wasn’t looking for a war; he was looking for a balm for his pride. But they lured him to the battlefield with false slogans of freedom. Five months later, he burned in the air raids, without knowing why he was there or what he was fighting for.

How did your family cope with this afterward?

His mother still hasn’t accepted it. Every March, she says, “Maybe he’s alive.” For us, it’s not just pain; it’s uncertainty. If we had seen his body, perhaps we would have found peace, but this not knowing is like poison. You can neither mourn nor hope.

If members of that group were standing in front of you today, what would you say?

I would say, why do you exploit a young man who is failed and desperate? Why do you deceive him? Why, when he dies, do you not even say where he is? Was my son your enemy? He was only searching for meaning, and you used that meaning for war.