The events following 9/11 ushered in a new phase for the concept of self-defense, where non-state threats, such as Kurdish armed groups, became a challenge to the principle of territorial sovereignty. International law experts believe that within the framework of international rules and based on the right to self-defense, Iran can counter these threats.

Exclusive Interview

The International Rules on the Use of Force; From the UN Charter to Modern Threats

In the post-World War II era, international law has attempted to regulate state relations by setting rules to prevent war. However, with the rise of non-state actors, fundamental questions have emerged about the adequacy of these frameworks.

Amirhossein Mohebali, a Ph.D. in International Law and a researcher at the Judiciary’s Research Institute, spoke with a reporter from the Iranian Kurdistan Human Rights Watch about various dimensions of human rights violations, including those against women and children, by anti-Iranian armed Kurdish groups based in Iraqi Kurdistan. He also discussed the negative and destructive impacts of these groups’ actions on the “right to development” in Kurdish-populated and border regions of western and northwestern Iran, from the perspective of international rules and law.

The full text of the interview is as follows:

The UN Charter and the Prohibition of the Use of Force

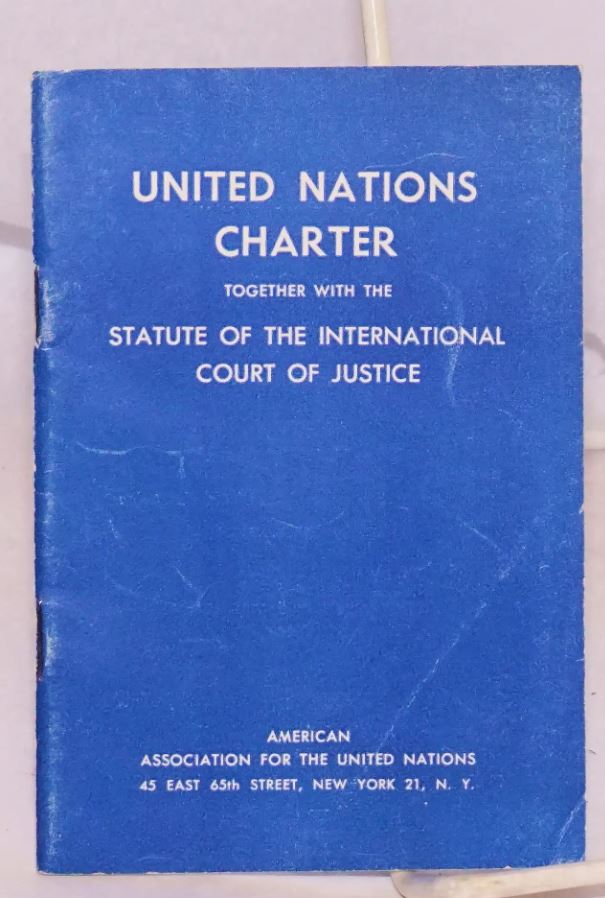

You are likely aware that the United Nations was established after World War II following conferences like those in San Francisco and Tehran. The organization was founded in 1945 based on its main charter. Article 2 of the charter outlines important principles regarding the conduct of states, one of the most fundamental of which is the prohibition of the threat or use of force. Paragraph 4 of this article explicitly prohibits any threat or use of force in international relations.

Exceptions: Self-Defense and Collective Defense

Conversely, there are two important exceptions mentioned in the same charter:

- Self-defense: Article 51 allows states to react defensively to an armed attack.

- Collective defense: Chapter VII, especially Article 42, authorizes the UN Security Council to organize collective military action to maintain or restore peace.

A Superior Rule, But Not Jus Cogens

The rule prohibiting the use of force is considered a fundamental and dominant rule in international law. Some even consider it a jus cogens (peremptory norm), but due to the exceptions mentioned in the charter itself, it cannot be deemed completely inviolable. Therefore, it is a superior but not a peremptory rule. Donald Trump’s repeated threats against Iran were a direct contradiction of this provision and a clear violation of Article 2, Paragraph 4.

The Evolution of War from Interstate to Non-State

When the UN Charter was written, wars were primarily defined as conflicts between states. However, after September 11, 2001, the nature of threats changed. Today, many attacks and conflicts are carried out by non-state and terrorist groups that do not fit within the traditional framework of the charter.

Self-Defense Against Non-State Threats

With the rise of militant groups, the question arose as to whether the prohibition on the use of force and the right to self-defense also applied to non-state actors. Although the charter did not initially consider such groups, in response to evolving circumstances, the Security Council, through Resolutions 1368 and 1373, recognized self-defense against non-state threats after 9/11.

The Conflict Between Self-Defense and State Sovereignty

This new interpretation raised a significant legal dilemma: Is it permissible, in response to an attack by a non-state group, to enter the territory of the country where that group is present? This question challenges the principle of territorial sovereignty.

- Accomplice State: If the host state directly supports or endorses the group’s actions, self-defense is permissible against the state itself.

- Unable or Unwilling State: If the host state is unable or unwilling to curb the group, the victim country may conduct limited and targeted strikes on the group’s positions within that territory.

Iran and Armed Groups in Iraqi Kurdistan

The same legal framework applies to armed groups opposing the Islamic Republic of Iran, such as KOMALA and the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (PDKI), which are based in Iraqi Kurdistan. If the government of Iraq or the Kurdistan Regional Government does not control or support these groups, Iran is legally permitted, under international law, to target their positions in a limited manner.

Bilateral Security Agreements

Security agreements, like the one between Iran and Iraq, primarily provide a basis for non-military and legal cooperation. These agreements must align with the general principles of international law and cannot override them. Provisions such as the extradition of criminals can serve as effective legal tools to confront terrorist groups.

The Absence of a Comprehensive Counter-Terrorism Law in Iran

One of the main challenges in the judicial pursuit of terrorism is the lack of a comprehensive domestic law in this area. Currently, Iran’s legal system not only lacks a specific definition for the crime of terrorism but also faces legal voids in pursuing international crimes like war crimes or genocide.

The Need to Pass a Comprehensive Counter-Terrorism Bill

A comprehensive counter-terrorism bill, if passed, could provide a precise definition of the crime of terrorism, establish legal elements, and clarify judicial processes. This bill would be a vital step towards empowering national judicial capacities in dealing with terrorists attacking Iranian interests or citizens.

International Capacities for Legal Pursuit

At the international level, although official judicial mechanisms face serious limitations, quasi-judicial mechanisms such as the Human Rights Council, thematic committees, and individual complaint procedures can be effective tools for documentation and legal follow-up. These mechanisms can initiate complaints and refer cases without the consent of governments, thereby exerting both political and legal pressure internationally.