Khaled Pourmohammadi: Life? There was no such thing as life there. The only thing I could experience in that environment was relentless and arduous work.

Migration and seeking asylum are complex and multifaceted issues that have always been accompanied by various challenges and consequences in different societies. In this regard, young people, especially in less developed regions, due to unsuitable economic, social, and political conditions, seek better life opportunities and a brighter future.

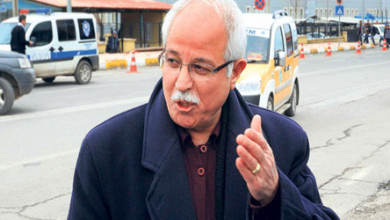

This process sometimes leads them into the clutches of illegal groups and paramilitary organizations that, with deceptive promises, guide them towards dangerous and unlawful paths. Khaled Pourmohammadi, a young man from Sarpol-e Zahab, is an example of such migrants who, under the influence of existing social and economic conditions, was looking for an opportunity to improve his life. With a tenth-grade education and currently working in a roadside restaurant, he fell into the trap of the PJAK group while searching for a way to immigrate to Europe.

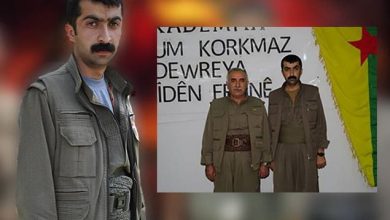

This armed group, which introduces itself as a political organization, in fact, exploits the dire economic and social conditions of young people, recruits them, and engages them in military and paramilitary activities.

This interview examines Khaled’s situation and how he joined this group. Furthermore, issues such as deception, exploitation of young people, and human rights violations in this process will be analyzed. This study demonstrates how social and economic conditions can push individuals toward dangerous choices and and highlights the necessity of attention to human rights and support for young people in facing such challenges.

Khaled Pourmohammadi, born on April 23, 1995, in Sarpol-e Zahab, with a tenth-grade education, is now working in a roadside restaurant. He was deceived by PJAK group’s social media pages regarding sending individuals to Europe, with the intention of migrating and seeking asylum there. In 2017, with the guidance of the group’s cadres, he illegally crossed the border. After six years of accompanying and cooperating with the armed PJAK group, he finally entered the country in January 2023 and surrendered himself to the police.

According to Mr. Pourmohammadi’s statements, during the six years he was a member of this armed group, he was constantly engaged in labor and digging tunnels inside the mountains. Eventually, after becoming exhausted from the existing conditions, he attempted to escape once and worked as a laborer in Sulaymaniyah for one year. He was then abducted by the group and returned to PJAK’s headquarters, where he was detained in the group’s prison for approximately six months.

However, when the area where he was imprisoned came under Turkish air attack, he, along with his guard named Hevidar (a Turkish girl who had been a PJAK member for 9 years and had also previously attempted to escape, but after being arrested, PJAK members had broken her leg and it had subsequently been plated; this also served as an additional reason for escape), fled the headquarters and surrendered themselves to the Asayish forces in Penjwen.

Interview with Khaled Pourmohammadi by Iranian Kurdistan Human Rights Watch Reporter:

Question: What made you decide to leave the country?

Khaled Pourmohammadi: “I am from Sarpol-e Zahab. When I only studied up to the tenth grade, I had to look for work. I didn’t have a stable job, and our financial situation wasn’t good. In those years, many people around me talked about seeking asylum and that one could go to Europe from Iraq. Like many other young people who were looking for a better life, I also started thinking about it. Through Telegram and Instagram, I came across a page that claimed it could help with going to Europe through the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. I didn’t know that the PJAK group was behind these promises, and I thought I was entering a legal path.”

Question: So, you were unaware of your connection with the armed and terrorist group named PJAK?

Khaled Pourmohammadi: “I had no information at all! They only talked about migration. They said they had a reliable channel, and I just had to come to Iraq for a while for my exit procedures to be completed. Without my family realizing, I crossed the border on May 24, 2017. Right then, a person from the group took me at the border, and from that moment, I realized the situation was not as I had thought. They took me to the Qandil Mountains and told me I had to become a member and there was no way back.”

Question: What was your reaction? Did you try to go back?

Khaled Pourmohammadi: “At first, I was shocked. I said I came for asylum, not to join an armed group in the mountains! But they said it was too late. They took my belongings, took my mobile phone from me, and took me to a remote area with no communication. They said I first had to train and then work. There was no way to contact anyone or go back, and I felt trapped.”

Question: How was your life during the six years you were a member of the group?

Khaled Pourmohammadi: “Life? There was no such thing as life there. The only thing I could experience in that environment was relentless and arduous work. From the very beginning, I was sent to the technical and excavation section. Every day and every night, we had to dig tunnels deep into the mountains, without even a moment’s rest. This work was not only physically but also mentally exhausting.

We received no wages, and there was no security for us. We felt trapped in a cruel and cold world. There wasn’t enough food, and we usually had to settle for a few simple and insufficient meals. In winter, the severe cold bothered us immensely. I often witnessed children getting sick or having fevers due to the cold, and there was no care or treatment for them.

We also didn’t have suitable clothes; many of us continued to work with only old and torn clothes. The conditions were so difficult that sleeping on the cold, hard ground itself became a challenge. We had no normal or comfortable place to sleep. In fact, our daily life had turned into a struggle for survival.

These conditions not only affected our physical health but also weakened our morale. With each passing day, hope for the future diminished, and we only thought about survival. This situation negatively impacted not only me but everyone else there. We lived in a dark and ruthless world where no sign of human life could be seen.”

Question: Was there discrimination in dealing with members?

Khaled Pourmohammadi: “Yes, there was a lot of discrimination. We, who came from Iran, were always considered lower class. Turkish Kurds, especially if they had years of experience, had the right to give orders and even ask us to do their personal chores. If we protested, we were threatened and sometimes punished; for example, our food was reduced, or we were transferred to dangerous areas.”

Question: Did you have a history of escaping?

Khaled Pourmohammadi: “Yes, after about five years, I was exhausted. My body was wasted, and my spirit was destroyed. At the first opportunity, I tried to escape, and I managed to get out of one of the headquarters and reach the city of Sulaymaniyah. There, I worked as a laborer for about a year; in buildings and sometimes in restaurants. I thought I had finally escaped that hell.”

Question: But you went back there again? How did that happen?

Khaled Pourmohammadi: “Unfortunately, yes. One day I was at work when a few members of the group found me. I don’t even know how they found out where I was. With force and threats, they put me in a car and took me back to the base. From that moment on, I was not only a member of the group but also considered a criminal.”

Question: How were you treated after you returned?

Khaled Pourmohammadi: “I was imprisoned for almost six months. In a dark room, with only an old blanket. They told me I had betrayed them and had to be punished. No attention was paid to my situation. It was there that I realized a group that claimed freedom and justice had no mercy even on its own members.”

Question: During that time, was anyone with you, or did you see anyone in a similar situation?

Khaled Pourmohammadi: “Yes, one of the prison guards was a girl named ‘Hevidar,’ who had 9 years of membership experience. She had also escaped before but was found and brought back. She recounted that after her escape, her right leg was broken and plated. She was in a lot of pain and had lost hope. She told me that if an opportunity arose, she would escape again. We gradually planned our escape together.”

Question: How did you manage to escape from that situation?

Khaled Pourmohammadi: “One day, during a Turkish air attack on one of the nearby headquarters, everything fell apart. We used this chaos and, along with a few others, escaped the area. We hid in the mountains and forests for a few days, and after enduring great hardships, we managed to reach the ‘Asayish’ forces in Penjwen. They took us in and held us for status review.”

Question: What happened after that? How did you return to Iran?

Khaled Pourmohammadi: “After the situation stabilized a bit and with some coordination, I was able to surrender myself to Iran in January 2023. I really didn’t know how they would treat me, but contrary to my fears, their behavior was legal and respectful. The judicial process was carried out, and the court issued a verdict for me, but ultimately I was acquitted and was able to return to normal life.”

Question: Now that you look back, how do you feel?

Khaled Pourmohammadi: “I feel bitter. Very bitter. I lost six years of my life in the worst possible conditions, separated from my family, my life, and my future. But today, I’m trying to live again. I’m working in a roadside kebab shop. Working is hard, but it’s honorable. The only request I have for young people is not to be deceived by the promises of social media and groups. Asylum, Europe, and a better life are not achieved through war, deception, and weapons.”