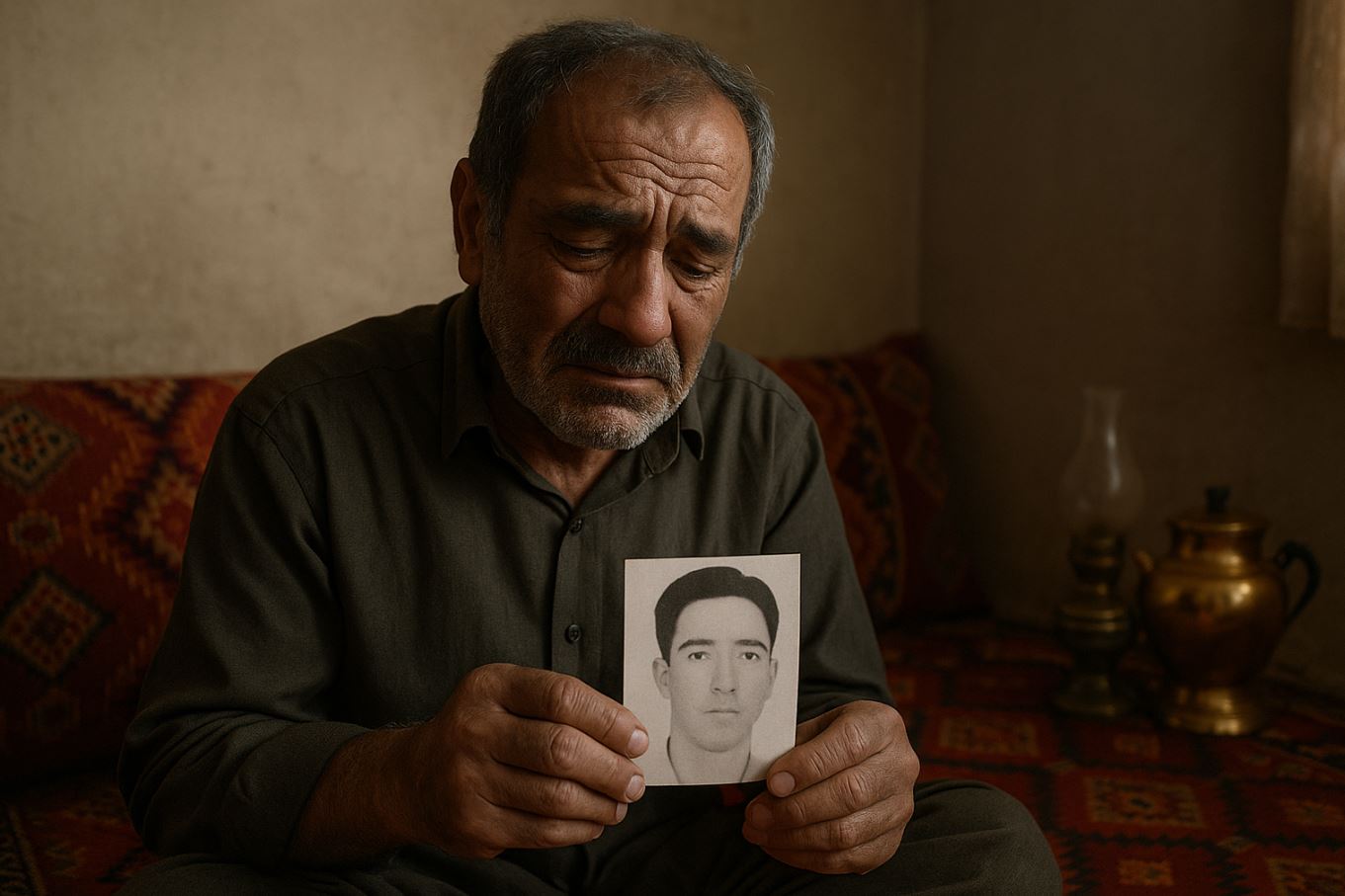

Yaser Mahmoudi’s Father: “It’s As If Our Son Never Existed. We Were Left Alone, With a Grief That Is Still Alive.”

Life is sometimes so unpredictable and challenging that it plunges people into profound depths of emotion. The story of Seyed Yaser Mahmoudi-Nasrabadi, a young man from a lush and delightful land, exemplifies one such challenge. Raised in a family with deep cultural roots, on the verge of starting a sweet new life, he suddenly found himself on a path that not only took him away from his family but also sealed his fate in a bitter way.

Seyed Yaser, son of Seyed Karim, was born in Qasr-e Shirin County. With big dreams and hopes for a bright future, he entered life. He held a diploma in electrical engineering and was determined to build a better future for himself and his family. However, fate did not unfold as he wished. Just one week after announcing his decision to marry, he faced opposition from his family. This opposition led him to make a dangerous choice.

His journey to Iraqi Kurdistan and joining the terrorist group PJAK became a turning point in his life. This decision not only affected his life but also broke his family’s hearts. His father, Seyed Karim, traveled to Iraqi Kurdistan four times, hoping to find his son and meet him, but each time he returned with a heart full of hope and eyes full of tears. Two years after the news of Seyed Yaser’s death in a Turkish bombing was released, his father is still searching for the truth—a truth that not only fails to relieve the pain of losing his son but also leaves unanswered questions in his heart: Was his son really killed? Was he alone in those last moments of his life or with his friends? And most importantly, does the love and hope he once held still exist? Where is his son buried?

Enforced disappearance is one of the most bitter and painful social realities that plunges families into despair and confusion. This phenomenon not only overshadows the life of the disappeared individual but also leaves a deep wound on the hearts of their loved ones who are searching for the truth and hoping for their return. This story is not only a reminder of a family’s pain and suffering but also illustrates the complexities of young people’s lives today and the challenges that can lead them to make wrong choices. Seyed Yaser, with all his aspirations, has become a symbol of young people who, in search of identity and meaning, may find themselves on dangerous paths.

It should be noted that Seyed Yaser was born in 1989, and according to PJAK, he was killed in a Turkish bombing approximately six years ago, with the news released two years ago. On March 11, 2015, he legally left the country through the Parvizkhan land border for Iraqi Kurdistan and joined the terrorist group PJAK. However, his family has had no information about his status during these years.

Please introduce yourself and tell us a bit about your family’s situation.

Seyed Karim Mahmoudi: I am Seyed Karim Mahmoudi-Nasrabadi, from Qasr-e Shirin County in Kermanshah Province. We have lived in this border region for years. My main work was farming and animal husbandry, but with difficult economic conditions, I sometimes work as a laborer. My family, like many border-dwelling families, lives a simple life. I have four children, and Yaser was my second son. He was always a calm and quiet person, not one for arguments or trouble.

Could you tell us more about your son, Seyed Yaser? What was his temperament and personality like?

Seyed Karim Mahmoudi: Yaser was born in 1989. He was a bright and lovable child with a diploma in electrical engineering, always looking for work to stand on his own feet. Although our financial situation wasn’t great, he tried to help with family expenses. He was interested in technical work, and at home, everyone relied on him. We never thought he would leave us without a word one day.

What prompted him to leave home? Did you see any signs of distress or a decision to leave in him?

Seyed Karim Mahmoudi: The truth is, I don’t know exactly what was going through Yaser’s mind. I just remember that about a week before he left, he shared something with us. He said he was considering a girl for marriage. We objected, not out of stubbornness, but because of what we knew about that family. Yaser was upset, and after that, he spoke less and was quieter than usual. But we never imagined that he had decided to leave home. Until a week later, he suddenly and without a word left home. And that was forever, towards an armed group….

When and how did you find out he had joined the PJAK group?

Seyed Karim Mahmoudi: After Yaser left, we searched for him extensively, from his friends and acquaintances to neighbors, but no one knew anything. Finally, through the Passport Office, we found out that he had legally crossed the Parvizkhan border into Iraqi Kurdistan. Initially, we thought he might have gone for work, but sometime later, news reached us from an acquaintance in the Sulaymaniyah region that he had joined the PJAK group. We couldn’t believe it; Yaser was neither political nor had he ever spoken about these groups.

What steps did you take to find or see your son?

Seyed Karim Mahmoudi: I traveled to Iraqi Kurdistan four times. Each time I went with hope and returned empty-handed. I went to several villages near the mountains where the group was located and spoke with intermediaries. Once, near Qaladze (Qal’at Dizah), close to one of their camps, I encountered a few members of the group and pleaded with them to just let me see my son. But they gave no answer and only said it was not a place for interference. They didn’t even allow me to write a letter for him or record my voice. The last time, I was threatened that if I pursued it further, I might get into trouble myself.

When did you hear the news of his death?

Seyed Karim Mahmoudi: About six years after he left, one night we were accidentally watching television when a report was broadcast on one of the satellite channels affiliated with this group. They were reading the names of those killed, and Yaser’s name was among them. They also showed his picture, and I froze. They never contacted us officially or personally; we only learned from television that our son was no longer in this world.

Do you have any information about his burial place or the details of his death?

Seyed Karim Mahmoudi: No, we still don’t know. No body was handed over to us, nor do we have a place for mourning. It’s not even clear whether he was actually killed or if his name was just announced as killed. This lack of information and uncertainty is worse than death; one can neither grieve nor have hope. We are suspended in a painful void.

How have these years been for you and your family?

Seyed Karim Mahmoudi: These years have been like an endless torment for my family and me. His mother goes to sleep every night with tears in her eyes, and I wake up every night with nightmares. Not only does the loss of our son pain us, but not knowing what they did to him has crushed us deeply. Many around us don’t dare to sympathize, as if they are afraid of the topic. Some even think he might have wanted to go. But we know that this decision was made in a moment of anger, and if there was a way back, he would surely have returned.

Have any official bodies or human rights organizations made efforts to help you during this time?

Seyed Karim Mahmoudi: No, no organization pursued it or helped. Neither the government nor international bodies. It’s as if our son never existed. We were left alone, with a grief that is still alive. No one has followed up on the fate of my son and many other young people in PJAK and other groups. They haven’t even contacted us once.

If you could send a message to your son today, what would you say?

Seyed Karim Mahmoudi: If I could send a message to Yaser today, I would say: “My dear Yaser, if you hear our voice anywhere, know that we are still waiting for you. If you are alive, please come back. And if you are not, I only wish you knew that we have always prayed for you. You made a mistake, but I am your father, and wherever you are, I still love you. I just wish I could, one more time, even at your grave, say a prayer.”